Human Genetic Modification

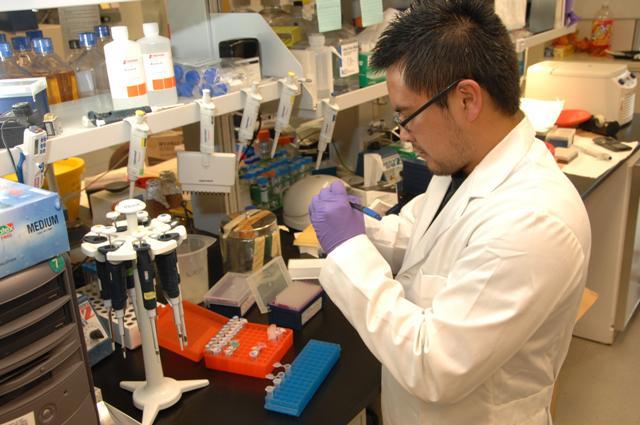

Human genetic modification (or “gene editing”) can be used in two very different ways. Somatic genome editing changes the genes in a patient’s cells to treat a medical condition. A few gene therapies are approaching clinical use but remain extraordinarily expensive.

By contrast, heritable genome editing would change genes in eggs, sperm, or early embryos to try to control the traits of a future child. Such alterations would affect every cell of the resulting person and all subsequent generations.

For safety, ethical, and social reasons, heritable genome editing is widely considered unacceptable. It is prohibited in 70 countries and by a binding international treaty. Nevertheless, in 2018 one scientist announced the birth of twins whose embryos he had edited. This reckless experiment intensified debate between advocates of heritable genome editing and those concerned it could exacerbate inequality and lead to a new, market-based eugenics.

Genome editing is a way of making changes to specific parts of a genome. Scientists have been able to alter DNA...

Public and policy conversations about heritable human genome editing often leave the impression that rules governing it are few and...