Assessing the Global Policy Landscape for Human Germline and Heritable Genome Editing

Public and policy conversations about heritable human genome editing often leave the impression that rules governing it are few and far between. Many news reports and scholarly articles present global governance as starting from a more or less blank slate; some also suggest that global agreement on this controversial issue would be unlikely. This view skims over some inconvenient facts, like the existence of the Oviedo Convention, a binding international treaty signed by 29 European countries, which prohibits heritable genome editing.

Even the recent report by the International Commission on Clinical Uses of Human Germline Genome Editing follows this pattern: It acknowledges the existence of the numerous laws about heritable genome editing only with the phrase “many countries” prohibit it, and mentions the Oviedo Convention only in a footnote.

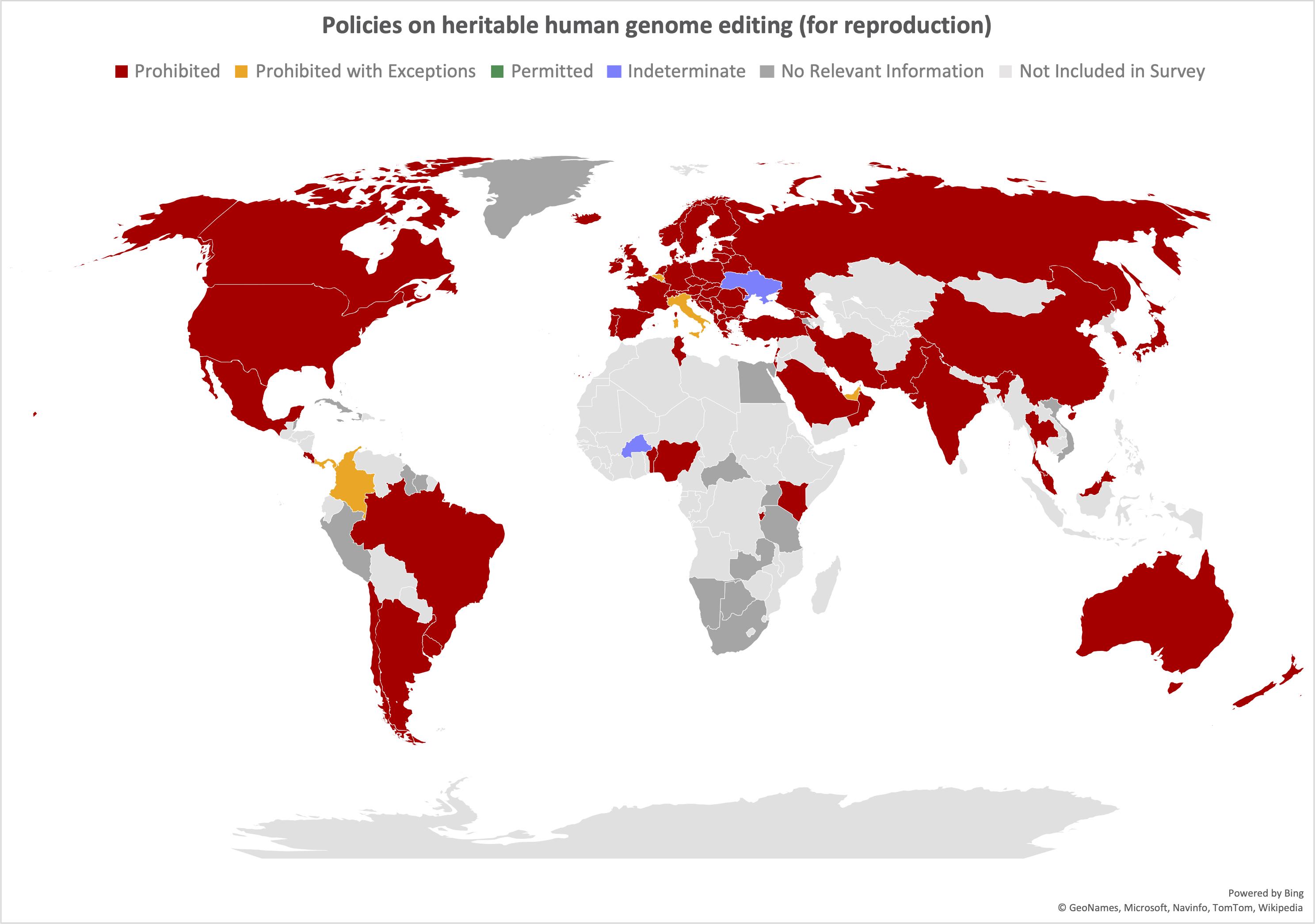

In an effort to amend unwarranted assumptions and incomplete information, we set out to produce a comprehensive picture of the existing global policy landscape on heritable genome editing. Our research, just published in The CRISPR Journal, shows just how much has been missing: Out of 106 countries we surveyed, 75 prohibit heritable human genome editing. Seventy prohibit it outright, while five allow for possible exceptions. Not a single one permits it.

Conducted by Françoise Baylis and Timothy Krahn of Dalhousie University, and myself and Marcy Darnovsky of the Center for Genetics and Society, this research is the most comprehensive study of policies on human genome editing to date, more than doubling the number of countries examined in previous studies.

We aimed to make our assessments as transparent as possible. Alongside the article reporting our results, we also published the tables listing the policy documents we reviewed for each country (with links to the original source); the excerpts we used to make our assessments; and our categorizations for both heritable human genome editing (for reproduction) and human germline genome editing (not for reproduction).

Here are some of the takeaways from our research.

Many more countries than previously acknowledged have policies relevant to heritable genome editing

Ninety-six of the 106 countries we reviewed have policies relevant to human genome editing. In total, we examined 126 policy documents (some countries had multiple documents). When it comes to heritable human genome editing — producing genetically modified gametes or embryos and using them to initiate a pregnancy that would result in the birth of a child with a modified genome — 78 countries have relevant policies. That’s more than 80% of the countries in our sample, and about 40% of the countries in the world.

There is near consensus on prohibition of heritable genome editing among countries with relevant policies

Of the 78 countries with relevant policies, a full 96% (75 countries) prohibit heritable human genome editing. Seventy prohibit it outright and five allow for possible exceptions. The remaining three countries were difficult to categorize (we called these “indeterminate”). In other words, the vast majority of countries with any kind of policy relevant to heritable human genome editing prohibit it. This is a striking degree of global agreement, and should be central to any future policy and public considerations.

The picture is quite different for human germline genome editing (not for reproduction) – in other words, producing genetically modified in vitro embryos or gametes in the lab but not using them to attempt a pregnancy. Most of the countries we reviewed (56) do not have policies on its permissibility or impermissibility. Of those that do, nineteen countries prohibit it, four prohibit it with exceptions, and eleven permit it. Six countries have policies that we categorized as indeterminate.

The absence of policies specifically addressing germline genome editing (not for reproduction) might be explained in a variety of ways. We might not expect countries to have legislation that explicitly permits specific experimental techniques, especially if they fall under another category of research, such as research on human embryos. Alternatively, it might mean that the country has other, higher priority legislative commitments in the context of limited policymaking resources.

The bottom line

Policy discussions of heritable human genome editing need to be based on transparent and accurate assessments of the current landscape. Approaching global governance with the assumption that there is a policy vacuum ignores the large number of countries that already have policies and the near-consensus among them, which suggests that it may very well be possible to come to global agreement. Any attempt to develop global governance strategies – or even meaningful international cooperation – that doesn’t acknowledge the policies already in place in dozens of countries is bound to fall flat.

If you’re interested in learning more, check out the full paper and the supplemental tables (available Open Access) in The CRISPR Journal. As more information becomes available, we’ll be updating the tables, which you’ll be able to find here: https://tinyurl.com/HumanGenomeEditingPolicies.

Image from: Françoise Baylis, Marcy Darnovsky, Katie Hasson, and Timothy M. Krahn. 2020. Human Germline and Heritable Genome Editing: The Global Policy Landscape. The CRISPR Journal 3(5): 365-377. http://doi.org/10.1089/crispr.2020.0082