Lab-Made Gametes Take Center Stage

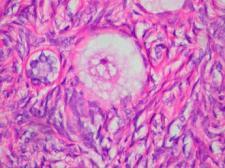

"Human Egg" by euthman is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

In late April, the National Academies held a three-day workshop on In Vitro Derived Human Gametes as a Reproductive Technology. Experts from a broad range of fields commented on the fast-developing science, its potential applications in assisted reproduction, and its social implications. Despite a focus on the significant technical challenges that remain in developing these techniques and the notable inclusion of several critical voices, the overall tone of the discussion was predictably one of approval. When introducing the session “Implications of IVG in Clinical Practice,” Hugh Taylor, past president of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine and member of the committee that organized the workshop, declared:“It’s not a matter of if this technology will be available for clinical practice, but just a matter of when.”

The science

In Vitro Gametogenesis (IVG) is an umbrella term covering several methods for the production of artificial gametes – deriving eggs or sperm in the lab from either stem cells or somatic cells (e.g. skin or blood cells) that are turned into pluripotent stem cells.

Several teams of scientists, many working in Japan, have made significant progress with these methods in mice, including producing live births from in vitro derived gametes. Work on human cells has proved more challenging. Some of the major stumbling blocks discussed at the workshop include:

- Getting gamete precursor cells to continue to develop and mature.

- Screening and testing. Scientists still lack ways to check the genetic sequence of a single cell without destroying it. And at this time the only way to test whether lab-derived gametes are functional, meaning they could achieve fertilization and normal embryonic development, is to actually use them to create an embryo. Scientists expressed that both of these constraints pose problems for testing whether IVG has been successfully achieved.

These and many other technical challenges would need to be resolved before scientists could make any substantive claims about whether IVG is effective or safe enough to enter pre-clinical or clinical research.

The fertility industry

Despite some scientists’ more targeted and circumspect assessments, clinicians in the fertility industry and biotech entrepreneurs are clearly salivating over the prospect of rolling out this speculative technology on a mass scale. Repeated claims at the workshop that IVG will help “millions of people” pointed to anticipation of an expansive range of expected uses and vast potential markets, including:

- Age-related infertility (IVG could potentially allow women to have genetically related children into their 70s or beyond, particularly by employing a gestational surrogate. This was pointed to as the largest group of potential users.)

- Same-sex couples and transgender or intersex individuals who desire a child genetically related to both partners

- Individuals who are infertile due to treatment for cancer, bone marrow transplant, etc.

- Anyone who desires a less burdensome alternative to IVF

- Generating large numbers of embryos in order to screen for health risks or desired traits, including using polygenic risk scores

- Generating an unlimited supply of gametes or embryos for heritable genome editing

These predictions are way ahead of the science, but they are already being used to drive hype and push back against potential regulation or restrictions.

Further, much of the IVG research (particularly in the US) is happening in private industry, where developments are patented and findings are not published. Startups funded by Silicon Valley venture capital and “effective altruist” funds with ties to longtermism and other pernicious ideologies are leading the way. They operate without oversight by regulators or even the standard forms of scientific self-regulation, while private investment and profit motives are sure to encourage unsubstantiated marketing claims and rapid commercialization.

Indeed, while academic researchers’ estimates about when IVG might be ready for use in initial human experiments varied wildly, from “nowhere close” to 5-10 years, Conception Biosciences, headquartered in Berkeley, claimed in their presentation that they would achieve “proof of concept” lab-derived human eggs in 1-2 years.

What will be the impacts of developing IVG within companies and startup cultures, particularly when they are driven by private equity and venture capital funding and their work lacks transparency due to patents and attempts to protect intellectual property?

Ethical, legal, and social issues

The workshop organized by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) was billed as exploring the “ethical, legal, and social issues” raised by using IVG for reproduction. Given the early state of the science, it’s laudable that NASEM featured these issues prominently, inviting scholars and a few advocates with a wide range of perspectives to speak. However, as usual, the time given to detailed scientific presentations far outweighed the time for social scientists, ethicists, and advocates.

There was at least one glaring absence: voices and perspectives from the disability community. Several panelists referenced the need to have people with disabilities in conversations about IVG and pointed to some of the concerns disability communities have expressed, but the unplanned absence of the lone invited disability studies scholar meant that essential perspectives fell off the agenda. It was an outrageous omission not to have disability perspectives – plural – at the table.

The health and reproductive rights of women were frequently referenced but deserved deeper discussion. The risks and burdens of egg retrieval and IVF were cited as motivations for developing IVG, despite little past acknowledgement of these risks and the dearth of research on long-term health effects. The US Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision was frequently invoked as potentially having a chilling effect on IVG research. Less discussed were the ways that pursuing IVG in the context of severe restrictions on reproductive rights and decision-making in the US produces a system that promotes nearly unlimited opportunities for some people to pursue genetic parenthood, while depriving others of even basic decisions about reproduction and bodily autonomy.

The promise of shared genetic parenthood for LGBTQ+ couples is one of the enticements that proponents are holding out to encourage support for IVG. But there are a range of views in the LGBTQ+ community and it’s important to reflect on complex questions coming from LGBTQ advocates, such as: Do fairness and inclusion mean providing access to methods of forming families that are the same as heterosexual couples? Or do fairness and inclusion mean pushing back against privileging genetic relatedness as the definition of family? Does encouraging use of these radical, potentially very risky procedures in the name of genetic relatedness really serve LGBTQ families?

Some of the deepest concerns are raised by the prospect of using IVG to produce a nearly unlimited supply of gametes and embryos that could then be ranked and selected according to proprietary polygenic risk score algorithms or subjected to genome editing. The financial and ideological connections between IVG startups and the pronatalist “hipster eugenics” movements gaining popularity in Silicon Valley that support human enhancement also raise significant concerns. There are strong parallels with the many reasons scientists, bioethicists, social justice advocates, and others believe heritable genome editing should remain off limits.

Not all uses of IVG would involve heritable genome editing, but many could. Given the overlaps, more attention is needed to when, how, and why genome editing and IVG should be discussed together or separately. Manipulating the genes and traits of future children and generations is prohibited in at least 70 countries. The recent concluding statement of the Third International Summit on Human Genome Editing reiterated that heritable genome editing “remains unacceptable” and that extensive discussion in needed about whether it should be used at all. Why would discussions of IVG start from the assumption that it will and should be developed for use in reproduction?

The National Academies workshop on IVG covered an impressive amount of ground over the three days, including devoting significant attention to societal risks and social justice concerns raised by these emerging technologies. Even so, key perspectives were not included and many of these discussions clearly need to continue at a deeper level. Future Biopolitical Times posts will explore these issues in more detail.