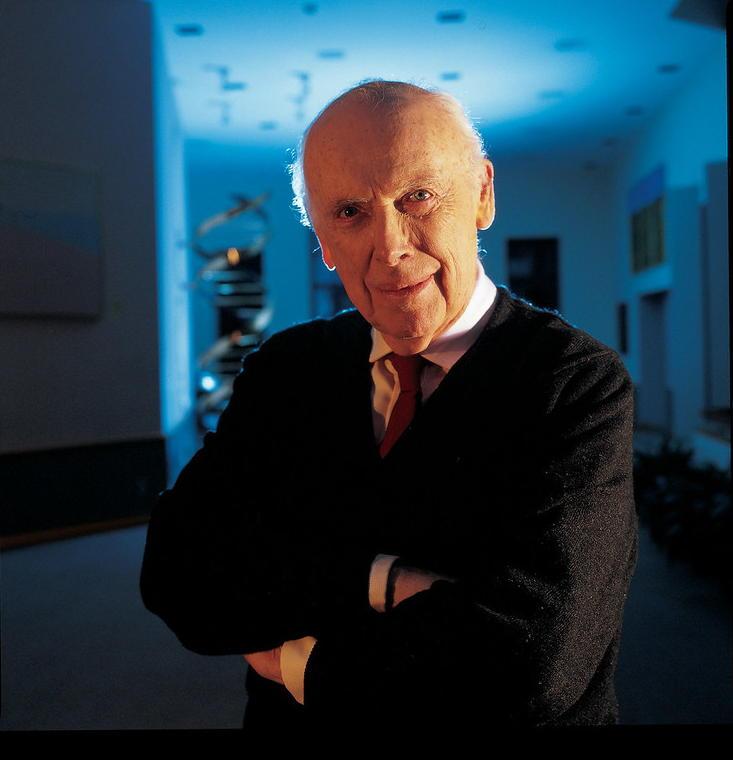

In Memoriam: James Watson, 1928–2025

Public domain portrait of James D. Watson by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory

and the National Human Genome Research Institute on Wikimedia Commons

James Watson, a scientist famous for ground-breaking work on DNA and notorious for expressing his antediluvian opinions, died on November 6, at the age of 97. Watson’s scientific eminence was primarily based on the 1953 discovery of the helical structure of DNA, for which he, Francis Crick and Maurice Wilkins shared the 1962 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. (Rosalind Franklin deserved to share it but had died of ovarian cancer in 1958.) Watson later became director of the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory and for two years headed the Human Genome Project.

His death was instantly global news and it is quite possible that his reputation will never recover. The New York Times, for example, referred to his “racist views” at the top of their report, and Nature’s first paragraph includes a reference to “contentious remarks about race.” Watson had read The Bell Curve, published in 1994, and evidently bought into its scientific racism. A lecture Watson gave at UC Berkeley in 2000, reported on by Tom Abate of the San Francisco Chronicle at the time and still available here, “provoked a scientific controversy by suggesting there are biochemical links between skin color and sexual activity and between thinness and ambition.”

Watson did get to write his own version of the research that led to the Nobel, in a 1968 book titled The Double Helix, which Crick dismissed as “a contemptible pack of damned nonsense.” Crick added in the same 1970 interview that Franklin would have discovered the double helix “certainly in three months” (and maybe less) without Crick and Watson, and independently Linus Pauling might have too.

Jon Cohen wrote a post-mortem remembrance in Science, under the headline “James Watson: Titan of science with tragic flaws.” He held “unrepentant racist views that cost him his job at CSHL [the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory] in 2007 and, in 2019, led the institution to revoke his emeritus status and condemn him for ‘the misuse of science to justify prejudice.’ He also was lambasted for sexism.” Cohen interviewed Nathaniel Comfort at length, who noted that

“He had very old-fashioned ideas about women, a kind of 1920s view about women into the 1960s. Among the top scientists, he treated women and men equally. But if they were second tier or mediocre, he would treat the women worse than the men.”

In 2019, the distinguished journalist Sharon Begley provided more detail about the break with CHSL. Before her untimely death in 2021, she wrote the 2000-word obituary that STAT published, with possibly the best headline of all:

James Watson, dead at 97, was a scientific legend and a pariah among his peers

Retired MIT professor Nancy Hopkins, whom Watson had encouraged to pursue an academic career, told Torie Bosch on the STAT+ podcast that he was a “remarkable man, a genius, a true genius, a giant — and with flaws that we can’t understand”:

“At around age 70, he began to go down this road. And it got worse and worse. And I have no explanation for it. I really don’t,” she said. “I think that he sort of reverted to the simplistic idea [in which] he wants to find a gene that explains everything. He went back to some childish view of genes that we had when we were young.”

Moreover, she said, Watson “explained” that:

“If you want to be a great scientist you have to be a shit, and women aren’t.”

In his prime, Watson considered himself to be “up there with Darwin.”

Considered all at once, the cumulative controversies resurfaced by Watson’s death may destroy what is left of his scientific reputation. Nathaniel Comfort suggested in the New York Times that they already have. Or perhaps, given the tenor of the times, he will once again be acclaimed, in what seems to be an increasingly sexist and racist society, as the truth-teller he thought he was.