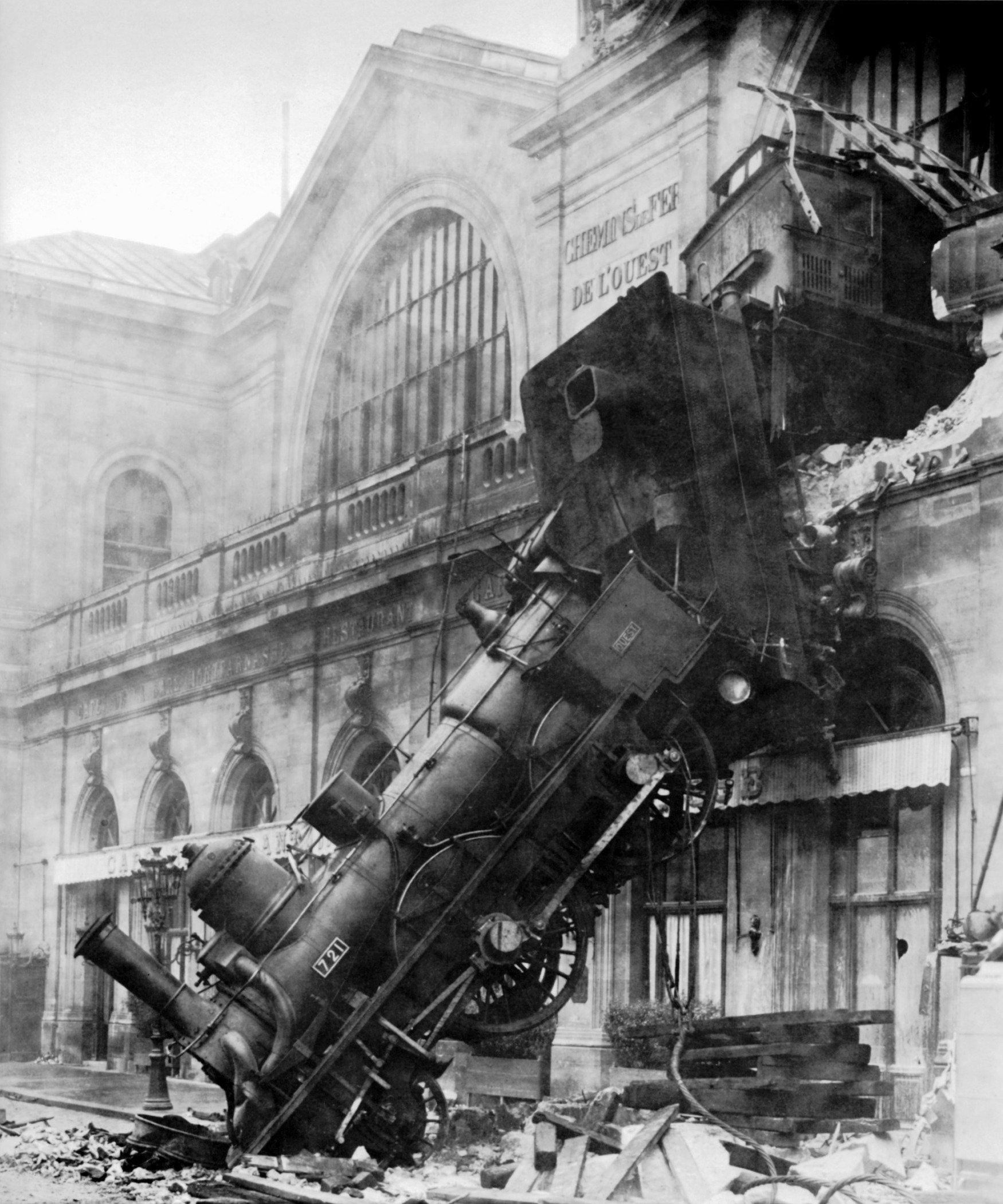

Rigorous Pathway or Runaway Train?

August 14, 2019, marked the first meeting of another committee on heritable genome editing that is composed mostly of scientists: the International Commission on the Clinical Use of Human Germline Genome Editing, a joint effort of the US National Academies of Science (NAS) and Medicine (NAM) and the UK Royal Society. The commission is tasked with developing “a framework for considering technical, scientific, medical, regulatory, and ethical requirements for germline genome editing, should society conclude such applications are acceptable.” It will specifically focus on the scientific issues involved, but may also consider “societal and ethical issues, where inextricably linked to research and clinical practice.”

The commission originated in the statement made by the organizers of the Second International Summit on Human Gene Editing, held in Hong Kong in November 2018, just days after the world was shocked by He Jiankui’s announcement that gene-edited twins had been born. The statement condemned He’s experiments as “irresponsible,” but went on to proclaim that “it is time to define a rigorous, responsible translational pathway toward” clinical trials of germline editing.

But is this “rigorous pathway” more like a runaway train?

CGS said at the time—and continues to say—that the question at hand is whether heritable human genome editing ought to be used at all, not how best to move it into the clinic. And we were not alone in saying this. A civil society statement organized by CGS and Human Genetics Alert called on the Summit organizers to:

(1) condemn in clear terms the rogue actions of the researcher who has taken it on himself to make a hugely consequential decision that affects all of us; and (2) call on governments and the United Nations to establish enforceable moratoria prohibiting reproductive experiments with human genetic engineering.

Over 150 individuals and organizations signed the statement. Since then, there have been further calls from prominent groups of scientists, bioethicists, and biotech industry executives for a moratorium on heritable gene editing (for examples, see 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6).

But the commission’s mandate is to double down on the matter of how, and to lay out in the most detail yet how to get to clinical uses of germline editing.

As Eric Lander and others pointed out in their call for a moratorium, the permissive tone taken by the 2017 report from the National Academies helped enable He to think that he was in line with mainstream ethical norms on human germline editing (or at least to claim he did). Recent statements by NAS president Victor Dzau and other authors of the NAS report suggest that what they are attempting with the new commission is a “do-over” that will prevent future He-like incidents.

They have missed the point. What is needed is a clear signal that no one should go ahead with clinical uses of heritable human genome editing, especially not without broad societal consensus. Scientific self-regulation is unlikely to provide this signal, as we saw with the failure of some five dozen scientists, clinicians, and entrepreneurs to stop He’s plans by notifying authorities or making them public.

In fact, in a Science editorial in December 2018 that proposed establishing an international commission, Dzau (along with Marcia McNutt and Chunli Bai) jettisoned the standard of broad societal consensus in favor of what they called “broad scientific consensus.” They did later think better of taking that position and affirmed a commitment to waiting for broad societal consensus. And the statement of task for the NAS/NAM/Royal Society commission includes a caveat that the framework developed would apply “if society concludes that heritable human genome editing applications are acceptable.”

But it’s not at all clear that this commitment is sincere or significant. The bodies that established the international commission haven’t made any provisions—or provided any resources—for developing ways to foster the kind of meaningful and inclusive public discussions that are so urgently needed. And it seems likely that once a framework for clinical use has been proposed, scientists who are eager to pursue heritable genome editing will hit the ground running. Will they really wait to see if society finds it acceptable, especially in the absence of any serious effort to ask or answer this question?

There were a few attempts at the meeting to pump the brakes. Early in the day, Carrie Wolinetz, Associate Director for Science Policy at the National Institutes of Health, said that the scientific community is guilty of paying lip service to broad societal engagement when, in reality, most scientists just want people to agree with their views. She reiterated that if must still be on the table and that the commission must be open to the possibility that society may hear all the arguments and decide against germline modification. She also went off-script and said, speaking both as a clinician and as a mother who has lost a child to a genetic condition, that she personally doesn't think a compelling case has been made for germline editing thus far.

Most of the day’s panels focused on lessons from work on somatic gene therapies that can be applied to germline modification. In a panel titled “Lessons from the Field,” Matthew Porteus laid out his objections to germline editing on technical grounds, while concluding that the social and ethical concerns are perhaps even more important. The CEOs of Sangamo and Editas discussed why their gene-editing companies have no interest in pursuing heritable genome editing.

A later session on regulation included a presentation on somatic gene editing by FDA representative Dr. Denise Gavin, who confirmed that the FDA does not have policy mechanisms for preventing off-label uses of human gene editing, and has limited enforcement options in any case. In a final session on patient perspectives, Sharon Terry of Genetic Alliance made another plea for meaningful public engagement, and reported that there is not a great deal of support for heritable genome editing in the patient communities with which she works.

Will the commission members take seriously the cautions and skepticism of these speakers and their own acknowledgment of the importance of societal consensus? Or will they pursue the plan to lay out exactly how heritable genome editing can make its way to clinical use? As we said in our civil society statement to the organizers of the Hong Kong summit, “If the summit and other scientific bodies do not act, it will fall to civil society and policymakers to do so, in order to ensure the avoidance of disastrous consequences for global society.”