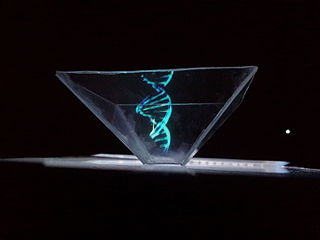

Crispr Therapeutics Plans Its First Clinical Trial for Genetic Disease

By Megan Molteni,

Wired

| 12. 11. 2017

In late 2012, French microbiologist Emmanuelle Charpentier approached a handful of American scientists about starting a company, a Crispr company. They included UC Berkeley’s Jennifer Doudna, George Church at Harvard University, and his former postdoc Feng Zhang of the Broad Institute—the brightest stars in the then-tiny field of Crispr research. Back then barely 100 papers had been published on the little-known guided DNA-cutting system. It certainly hadn’t attracted any money. But Charpentier thought that was about to change, and to simplify the process of intellectual property, she suggested the scientists team up.

It was a noble idea. But it wasn’t to be. Over the next year, as the science got stronger and VCs came sniffing, any hope of unity withered up and washed away, carried on a billion-dollar tide of investment. In the end, Crispr’s leading luminaries formed three companies—Caribou Biosciences, Editas Medicine, and Crispr Therapeutics—to take what they had done in their labs and use it to cure human disease. For nearly five years the “big three’ Crispr biotechs have been promising precise gene...

Related Articles

By Pete Shanks

| 02.27.2026

Last month, we published “The Shameful Legacy of Tuskegee” which focused on a proposed experiment in Guinea-Bissau. The study’s plan echoed the notorious Tuskegee disaster, withholding safe, effective vaccines against hepatitis B from some newborns while inoculating others. It was to be financed by the U.S. but performed by a controversial Danish team. That project provoked a multi-national outcry, leading to a remarkable response from the World Health Organization:

WHO has significant concerns regarding the study’s scientific...

By Jenn White, NPR | 02.26.2026

By Vittoria Vardanega, SWI swissinfo.ch | 02.13.2026

In recent years, sperm donation has produced family trees of unprecedented size, stretching across countries and, in some cases, continents. Stories of “mass donors” have captured public attention, most recently through the Netflix documentary series, The Man with 1,000 Kids...

By Kiana Jackson and Shannon Stubblefield, New Disabled South | 02.09.2026

"MC0_8230" via Wikimedia Commons licensed under CC by 2.0

This report documents a deliberate assault on disabled people in the United States. Not an accident. Not a series of bureaucratic missteps. An assault that has been coordinated across agencies...