Aggregated News

Like millions of other Americans, Victoria Gray has been sheltering at home with her children as the U.S. struggles through a deadly pandemic, and as protests over police violence have erupted across the country.

But Gray is not like any other American. She's the first person with a genetic disorder to get treated in the United States with the revolutionary gene-editing technique called CRISPR.

And as the one-year anniversary of her landmark treatment approaches, Gray has just received good news: The billions of genetically modified cells doctors infused into her body clearly appear to be alleviating virtually all the complications of her disorder, sickle cell disease.

"It's wonderful. It's the change I've been waiting on my whole life," Gray told NPR, which has had exclusive access to chronicle her experience over the past year.

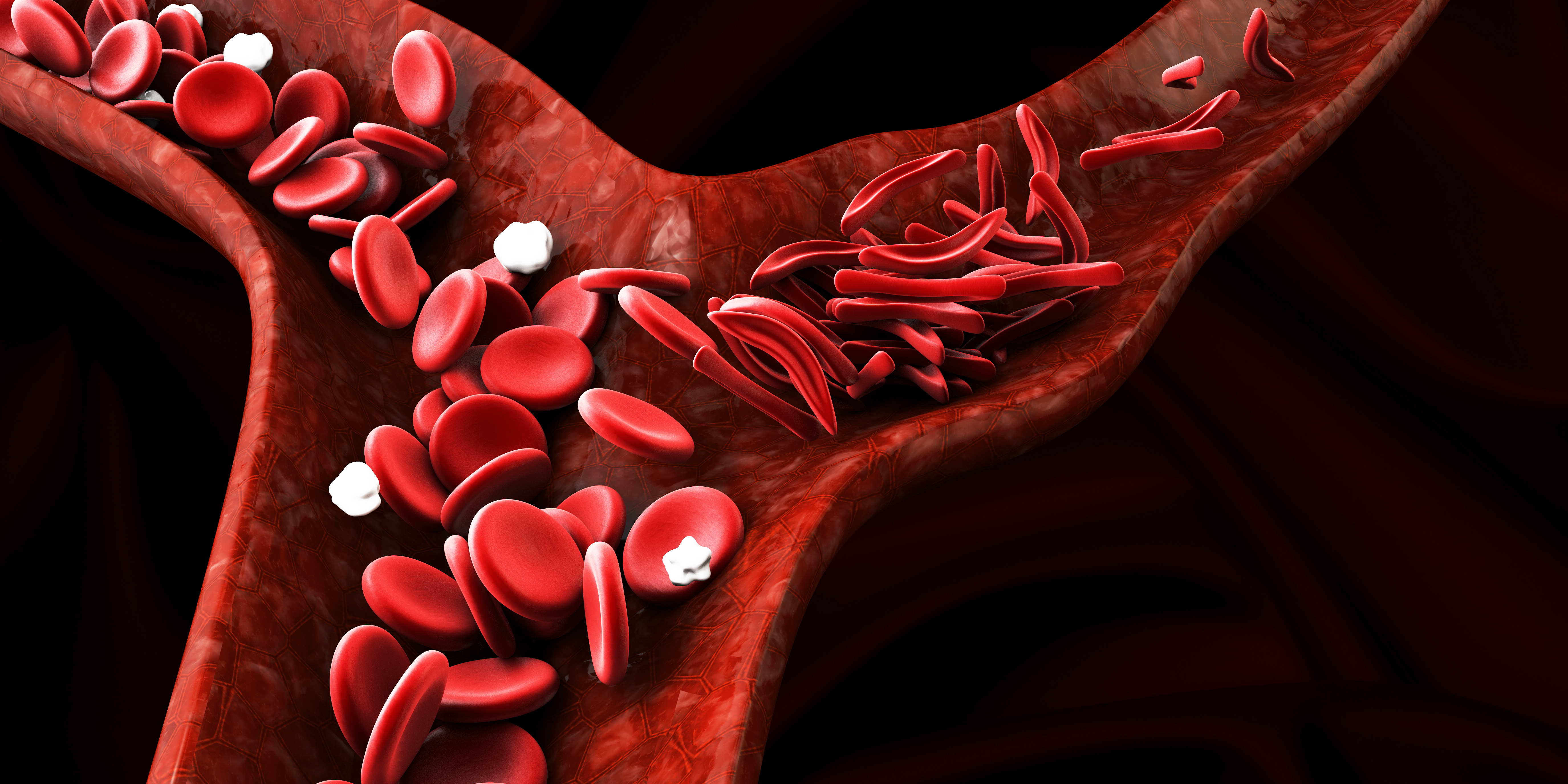

Sickle cell disease, a rare blood disorder that disproportionately affects African Americans in the U.S., can be difficult to treat effectively.

The last time NPR spoke with Gray — in November — her doctors had just gotten the first hints the treatment might be working. Now...