Aggregated News

Victoria Gray was wandering through the British Museum in London last week when she spotted a small wooden cross hanging on the wall.

"It's nice seeing all the old artifacts, especially the cross," Gray said. "Religion is something that I hold close to my heart, and my faith is what brought me this far."

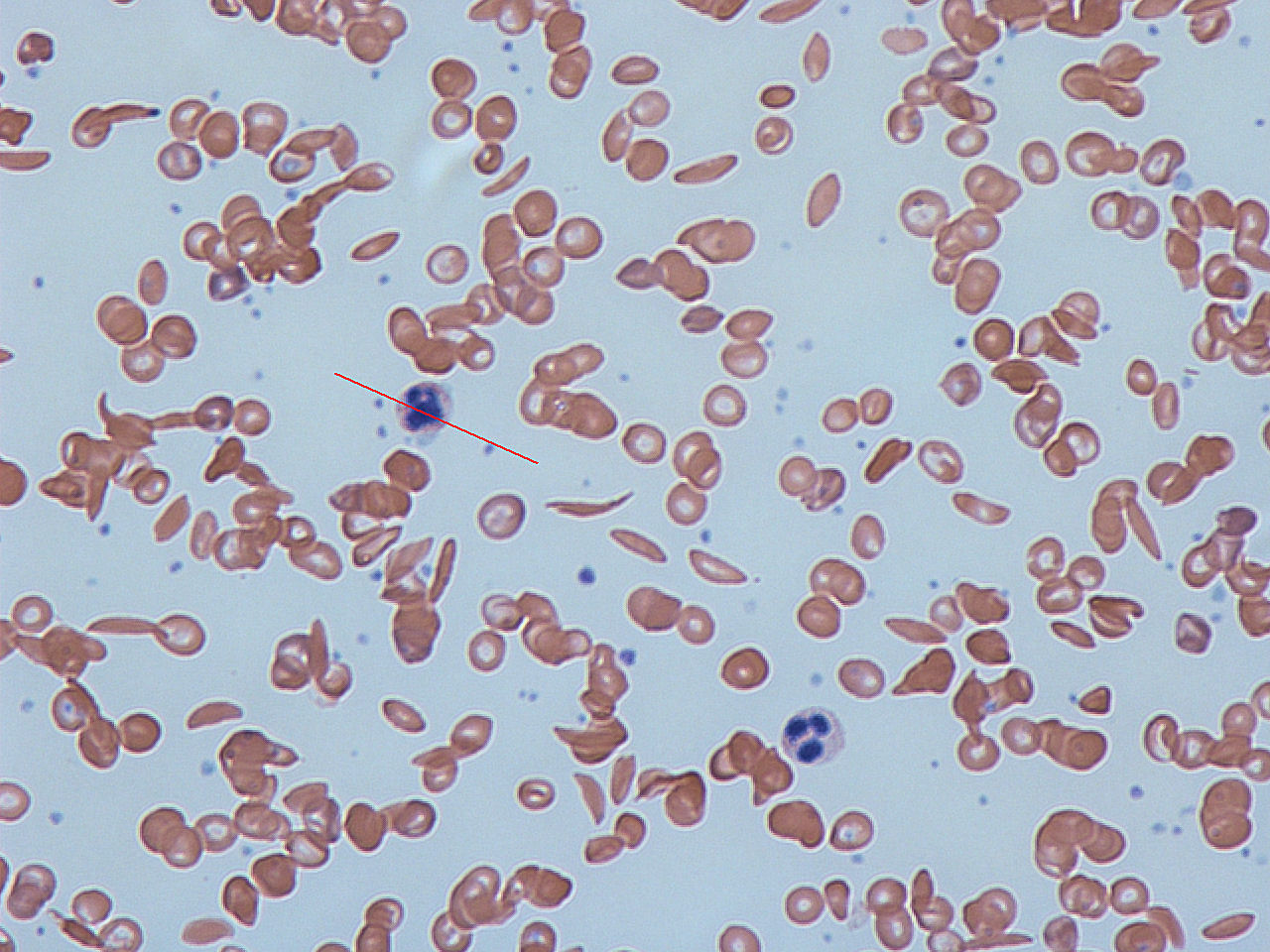

Almost four years ago, Gray became one of the first patients with a genetic disorder — and the first patient with sickle cell disease — to get an experimental treatment that uses the revolutionary gene-editing technique known as CRISPR.

Today, all of Gray's symptoms are gone, and she was in London last week to describe her landmark experience at the Third International Summit on Human Genome Editing. The summit brought together more than 400 scientists, doctors, patients, bioethicists and others from around the world to air the promise of gene editing as well as a host of thorny questions that the technology is raising.

"God did his part for what I prayed about for years," Gray said. "And together, hand in hand, God and...