With that result, Sheltzer and his team joined an expanding club of laboratories that have been forced to re-evaluate and repeat experiments, as the spread of CRISPR–Cas9 uncovers potential errors in data collected using...

Aggregated News

Scientists face tough decisions when the latest gene-editing findings don’t match up with the results of other techniques.

It seemed like the perfect plan.

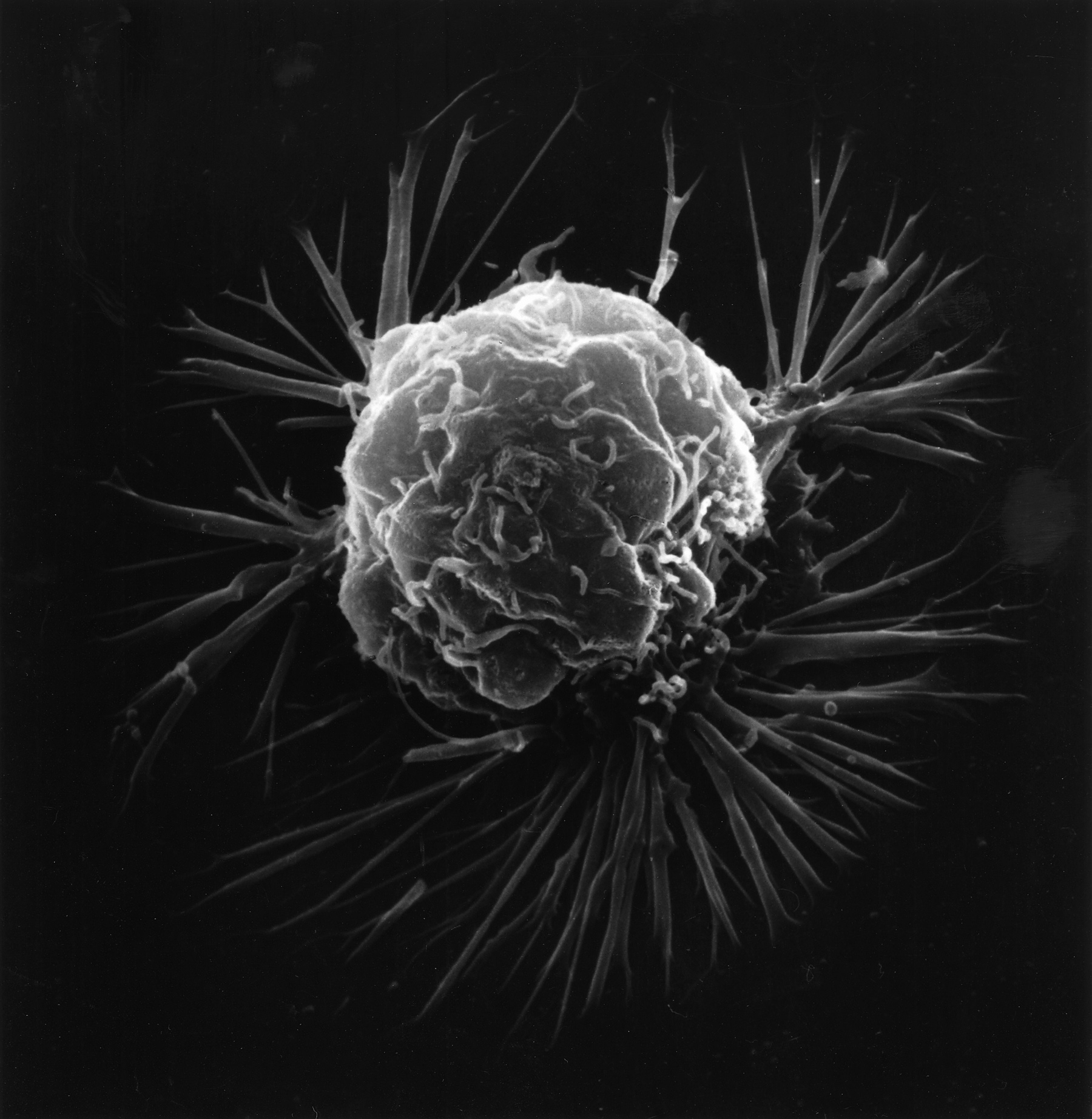

Jason Sheltzer, a cancer biologist at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York, was on the hunt for genes involved in tumour growth. He and his colleagues planned to disable genes using the popular gene-editing tool CRISPR–Cas9, then look for changes that reduced the rate at which cancer cells multiply. But they needed a control gene that would yield that same effect.

The literature suggested that the gene MELK was ideal: there was ample evidence that it is important in cancer-cell proliferation, and clinical trials are under way to test drugs that inhibit the MELK protein. But disabling the gene using CRISPR–Cas9 yielded no effect. “That threw a monkey wrench into our experiments,” says Sheltzer. “It brought everything to a halt.”