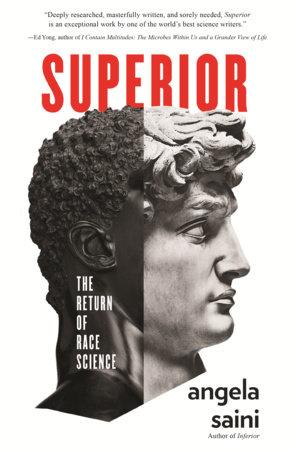

Book Review: Superior—The Return of Race Science

The use of modern genetics as a prop for centuries-old racist biases continues despite the best efforts of most scientists. As a native Londoner whose parents were born in India, Angela Saini is acutely aware of prejudice; she herself had rocks thrown at her when she was 10 years old, by boys telling her to “go home.” This, she says in the acknowledgments, “is the book I have wanted to write since I was a child.”

The tone throughout is calmly authoritative: that of the reporter she is, whose credits include the BBC, the Guardian (this 3700-word article is an excellent advertisement for the book), Wired, and Science, among others. She tells the story of genetic racism over the last century and more, including extensive interviews, not only with (for example) Jonathan Marks, who she rightly describes as “the academic many turn to for clarity when it comes to racism in science” (see here and here) but also David Reich, the geneticist who caused a considerable stir in 2018 by insisting that there are indeed genetic variations among “races” (his quotes). Saini is respectful of Reich, who is personally pleasant, in the interview but in a devastating conclusion to the chapter confronts him with the unashamed racism of James Watson, the living proof that a great scientist can also be a racist, sexist bigot.

The book covers the appalling history of racism, worldwide and throughout known history; it actually opens in that temple of empire, both ancient and modern, the British Museum. The focus is on more recent developments, and therein lies the book’s importance. She describes the efforts of Ashley Montagu, Richard Lewontin, and others to disprove the existence of biological race. But she also documents the reinvention of eugenics from the 1960s to the present by a small but tight-knit coterie of academics and privately-funded journals such as Mankind Quarterly, which kept the flame alive for the modern rise of nationalism.

She rightly enjoys the discovery in 2018 that sequencing DNA from “Cheddar Man,” a skeleton found in Britain that is about 11,000 years old, suggests that he was blue-eyed, curly-haired — and black (or at least, very possibly dark-skinned). This disturbed white British racists, but Saini uses it as a lead-in to discussing and demolishing still-prevalent simplistic ideas about supposed genetic heritage. (She dedicates the book to her parents, “the only ancestors I need to know.”)

This book is an invaluable resource, and my only real criticism is that the one-word title may give some the false impression that Saini endorses the idea that some groups are “superior.” But then her 2017 book about the sexist nature of much scientific research was called Inferior: How Science Got Women Wrong – and the New Research That’s Rewriting the Story. She is an author to watch.