The Biden Administration and Genetically Engineered Bioweapons Research

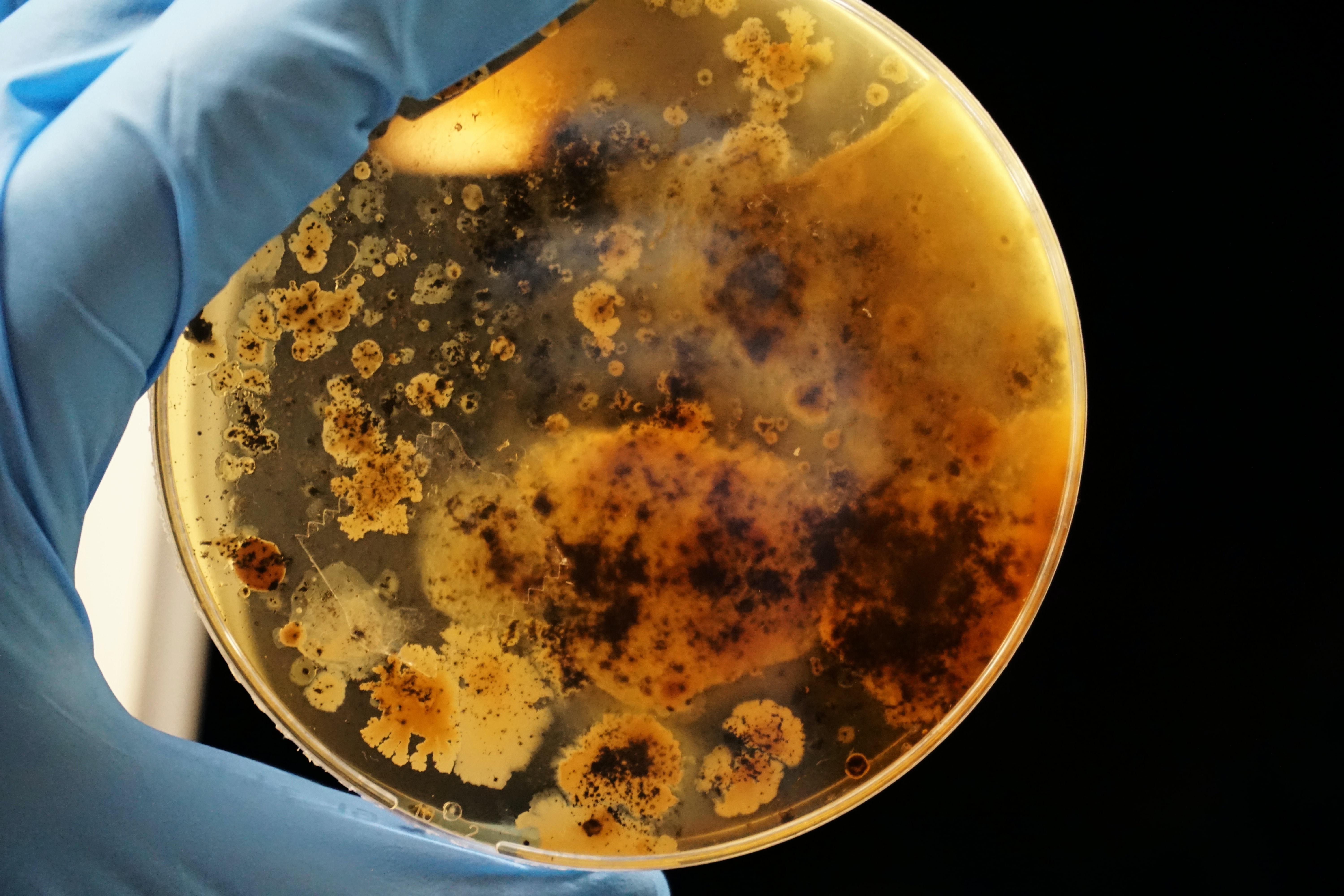

Photo by Adrian Lange on Unsplash

Living under the COVID-19 pandemic has justifiably created fear and uncertainty about germs and their evolving contagiousness and lethality. Against the backdrop of the natural evolution of the coronavirus and emerging new strains, many ruminate over further alarming scenarios—from questions about the coronavirus’s possible lab origins, to worry over the possibility of biohackers engineering new pandemic germs. New gene editing technologies like CRISPR make these scenarios all the more frightening, as they make it relatively easy to modify existing germs into bioweapons or even to create bioweapons from scratch.

Genetically engineered bioweapons are not a fictional or far-fetched notion. Many countries around the world, including the United States, have long engaged in research tinkering with germ weapons for so-called biodefense. In recent years, military researchers at the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency have used synthetic biology to design virus-infected insects for biodefense. In 2016, U.S. Director of National Intelligence James Clapper lent credence to concerns about the military implications of gene editing when he added it to a list of threats posed by “weapons of mass destruction and proliferation”—alongside biological, chemical, radiological, and nuclear weapons.

The incoming Biden-Harris administration promises a restoration of the role of science in government, particularly in environment and health. While I welcome this prospect, I join those who want more than a “return to normal.” The presidential transition provides an opening for advocates and activists to push back against systemic problems in the way U.S. science functions: an overemphasis on innovation without restraint or regard for social consequences, undue corporate influence, and unilateralism in international science policy. In this post, I focus on a technoscientific area deserving extra vigilance—gene editing and bioweapons.

Troubling innovations in bioweapons research

Bioweapons research long pre-dates the development of new gene editing tools like CRISPR. In the advent of the war on terror in 2001, the Bush administration had ramped up research involving lethal pathogens, including genetically engineered new germ variants. As I document in my just-published book Bio-Imperialism: Disease, Terror, and the Construction of National Fragility, this work is typically explained as a way to test new vaccines against or gain knowledge about possible new biological weapons. But as many critics point out, production of weaponized germs for research is largely an issue of semantics—the end result is that U.S. labs are creating dangerous bioweapons.

The Obama administration retreated from the prior administration’s wholehearted plunge into such risky research, and increased scrutiny of synthetic biology. But it was unwilling to assert effective oversight, issuing only guidance entreating scientists working in academic and corporate laboratories to screen suspicious orders of synthetic DNA. In the military realm, the Obama administration cut funding for bioweapons research, reallocating much of it to pandemic preparedness. But it continued the U.S. refusal to ratify the verification protocols of the Biological Weapons Convention, an international treaty that bans offensive bioweapons, because of objections to its inspection mechanisms by U.S. military and industry interests. In short, the Obama administration walked back the Bush era’s excesses, while leaving intact underlying structures of unfettered innovation, corporatism, and unilateralism.

Similar dynamics are likely with the transition about to take place. While the Trump administration was relatively silent about biotech innovation, in general it embraced profit-driven innovation aligned with its political agenda. For example, it threw significant policy focus, funding, and corporate partnerships into artificial intelligence and quantum science, areas of U.S. competition with China. U.S. militarism and unilateralism continued, albeit with a more bombastic tone and isolationist tack, perhaps best represented by U.S. withdrawal from the World Health Organization in May 2020, an eschewal of the prior approach of exerting global dominance from within the WHO.

What to expect from the Biden-Harris administration

As expected increases in funding from the Biden-Harris administration start flowing to the biosciences, it will be important to remain watchful for a reboot of bioweapons research and development.

On biotech and biomedical research more generally, some indications are promising. For example, Biden plans to ramp up COVID-19 testing, PPE distribution, and other low-tech endeavors to fight the pandemic, in addition to prioritizing development of vaccines and advanced treatments. Continued pressure to maintain these efforts—and stepping up pressure on the government to disentangle from corporate mandates—are, I believe, a great starting point for enacting a better path for science.

In areas relevant to bioweapons, there are reasons for more concern, among them Biden’s long record of supporting U.S. militarism, including his unapologetic support for the 2003 Iraq War. This, then, remains a key target for watchdog groups and activists: to push for further disinvestment in bioweapons research, along with fuller U.S. cooperation with international treaties—starting with U.S. ratification of the Biological Weapons Convention verification protocols at the upcoming 2021 conference.

Gwen D’Arcangelis is associate professor in Gender Studies at Skidmore College. Her work centers on the socio-political dimensions of science, medicine, and public health. Her newly released book, Bio-Imperialism: Disease, Terror, and the Construction of National Fragility, examines the gendered, raced, and imperial features of U.S. focus on bioterror and germ threats.